LINKED PAPER

Nesting ecology of a naturalized population of Mallards Anas platyrhynchos in New Zealand. Sheppard, J. L., Amundson, C. L., Arnold, T. W. & Klee, D. 2019. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.12656 VIEW

Mallards (Anas platyrhynchos) are everywhere. Through a combination of natural colonization events and human introductions, this duck species has managed conquer the world. During their global conquest, mallards adapted to novel environments and hybridized with local species, resulting in changes in ecology and genetic make-up (Lavretsky 2020). In New Zealand, for example, about 25,000 game-farmed mallards were introduced between 1940 and 1960. These birds established wild breeding populations and interbred with Pacific black ducks (Anas superciliosa). The genetic consequences of this introduction event have been well studied (Rhymer et al. 1994), but the ecological consequences remain largely unknown.

Nesting season

A team of international ornithologists studied the breeding ecology of mallards on two locations in New Zealand: the Southland Region on South Island and the Waikato Region on North Island. During 2014 and 2015, the researchers followed the comings and goings of 271 mallard nests. The monitoring efforts revealed that the nesting season on New Zealand (134 days) is significantly longer compared to North America (about 60 days, Greenwood et al. 1995). This prolonged nesting season can probably be attributed to the favorable conditions on New Zealand. Moreover, hybridization with local Pacific black ducks might have led to the exchange of genetic material that influences breeding behavior.

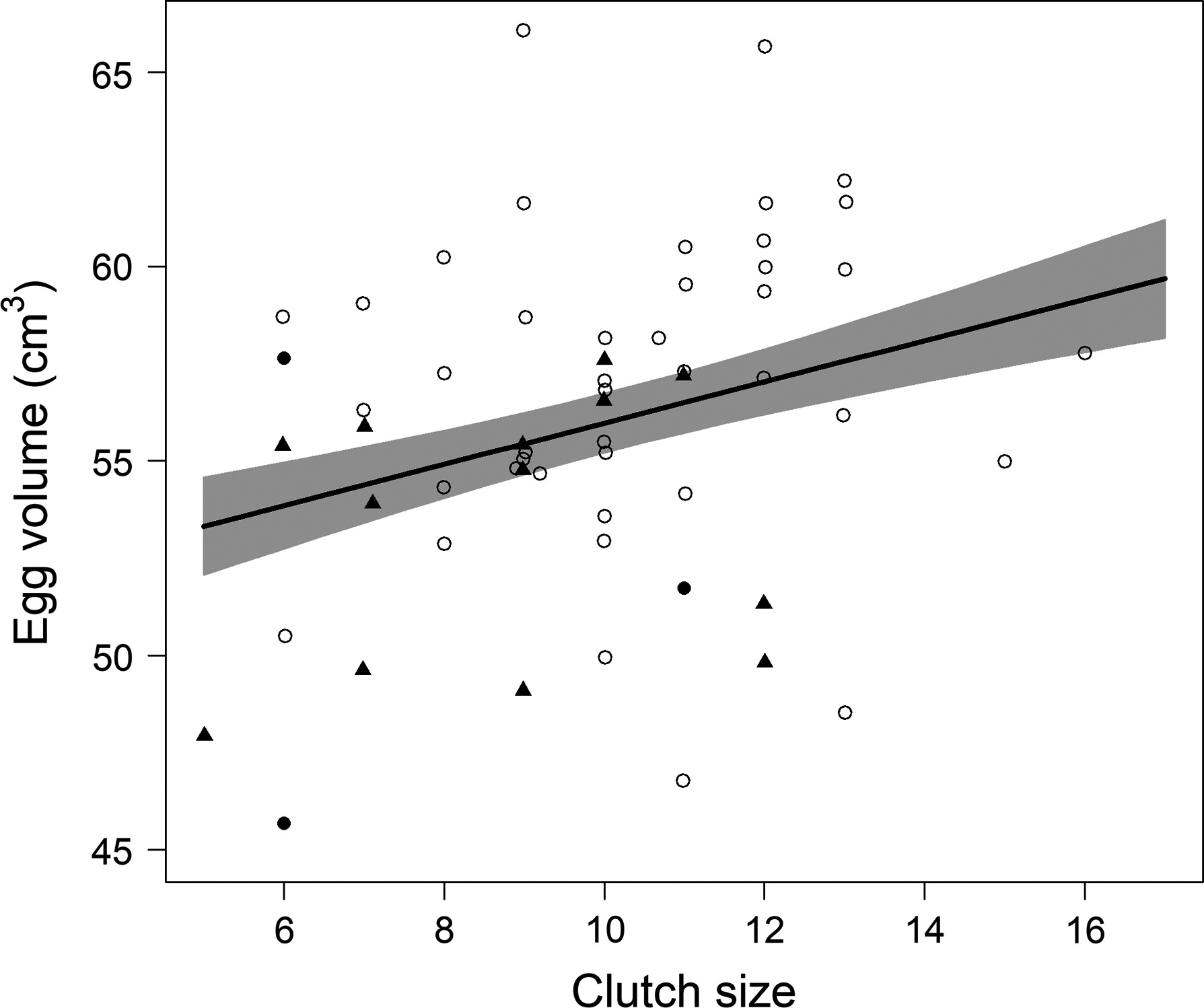

Figure 1 Female mallards on New Zealand lay big clutches with large eggs. An effect of their game-farm past?

Clutch size

Not only was the nesting season longer, New Zealand mallards also produced larger clutches with bigger eggs compared to mainland birds. This observation could be explained by the game-farm history of these ducks: past artificial selection for bigger eggs and higher fecundity might still be noticeable in the naturalized populations (Casas et al. 2012). In addition, estimates of nest survival were generally higher for New Zealand mallards compared to other populations worldwide. The high nest survival can probably be explained by lower depredation rates and the composition of predator communities on New Zealand. Mammals, such as stoats, rats and hedgehogs, did not co-evolve with the mallards as a prey and they are too small to deplete an entire mallard nest in one go (Dowding & Murphy 2001). Also the density of avian nest predators is much lower on New Zealand.

This study nicely illustrates how the ecology of introduced birds can rapidly shifts to match local conditions. These insights can be used to design better management strategies to conserve and protect New Zealand wildlife.

References

Casas, F., Mougeot, F., Sánchez‐Barbudo, I., Dávila, J.A. & Viñeula, J. (2012). Fitness consequences of anthropogenic hybridization in wild Red‐legged Partridge Alectoris rufa , Phasianidae populations. Biological Invasions 14: 295– 305. VIEW

Dowding, J.E. & Murphy, E.C. (2001). The impact of predation by introduced mammals on endemic shorebirds in New Zealand: a conservation perspective. Biological Conservation 99: 47– 64. VIEW

Greenwood, R.J., Sargeant, A.B., Johnson, D.H., Cowardin, L.M. & Shaffer, T.L. (1995). Factors associated with duck nest success in the Prairie Pothole Region of Canada. Wildlife Monographs 128: 1– 57. VIEW

Lavretsky, P. (2020). Population Genomics Provides Key Insights into Admixture, Speciation, and Evolution of Closely Related Ducks of the Mallard Complex. In: Population Genomics, p. 1-36 VIEW

Rhymer, J.M., Williams, M.J. & Braun, M.J. (1994). Mitochondrial analysis of gene flow between New Zealand Mallards (Anas platyrhynchos) and Grey Ducks (A. superciliosa). Auk 111: 970– 978. VIEW

Image credits

Featured image: Mallard Anas platyrhynchos | Alan D. Wilson | CC BY-SA 2.5 Wikimedia Commons