LINKED PAPER

Audubon’s Bird of Washington: unravelling the fraud that launched The birds of America. Halley, M.R. 2020. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club. DOI: 10.25226/bboc.v140i2.2020.a3. VIEW

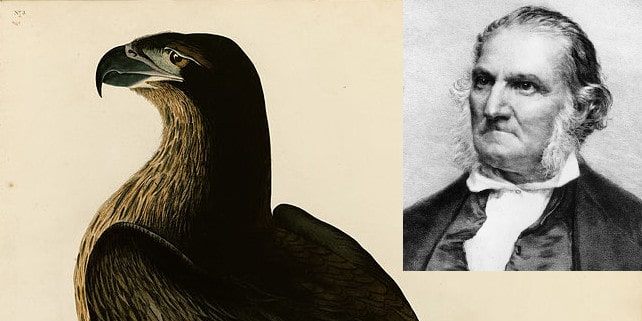

Fraud is defined as the “intentional perversion of truth in order to induce another to part with something of value”. In a recent peer-reviewed exposé, informed by a decade of research, I demonstrated beyond reasonable doubt that John James Audubon invented a new species of North American eagle, “the Bird of Washington”, to convince potential European investors of his genius. His painting was partially plagiarized, although he claimed it was based on a specimen, and he concocted (and published) false data and spread rumors to conceal the truth. Without this scheme, it is doubtful that Audubon would have garnered the investors needed to publish his major work, The Birds of America. This was fraud in its strictest sense.

More generally, fraud means “a person who is not what he or she pretends to be”. Audubon lied about where he came from, and what he experienced. There is incontrovertible evidence that he falsified data, published them in scientific journals and commercial books, plagiarized other artists’ works for his own financial gain, and invented new species to impress potential subscribers, and to “prank” potential rivals. Audubon’s famous banding (ringing) experiment, for which he has been hailed as the first bird bander in America, was at least partially fabricated, and perhaps entirely so. For nearly two centuries, we have frolicked in the largely fictional universe that Audubon created for us, conveniently brushing aside anyone who would dare whisper, “The emperor has no clothes.”

In the late 19th century, the name Audubon was co-opted by the emergent conservation movement, and his colorful images were employed as marketing and fundraising tools with great success. National Audubon Society became the powerhouse of bird conservation in the United States, and more than 500 regional societies now use the Audubon brand, although none has a direct historical connection to the man. These societies made (and continue to make) invaluable contributions to wildlife conservation, through efforts guided by science.

Meanwhile, the scientific reputation of their namesake has been steadily eroding with each new infraction exposed by historical research. The cumulative list of Audubon’s misdeeds is now extensive, and a recurrent pattern of anti-scientific behavior is evident, beginning with his opening plates and continuing throughout his career. Nevertheless, the organizations that use Audubon’s brand, and biographers who have relied on Audubon’s writings as historical sources, have routinely downplayed or ignored this mounting evidence, perpetuating the legend of Audubon the scientist, presumably to protect their own financial investments.

Figure 1 Audubon’s painting of The Bird of Washington, engraved for Plate 11 of The Birds of America. Originally claimed by Audubon to be a different, significantly larger and already rare species, most subsequent ornithologists assumed it was a misidentified (and incorrectly drawn) immature Bald Eagle, Haliaeetus leucocephalus. However, Halley (2020) has shown it to be a case of scientific fraud, based not on a specimen as Audubon claimed, but a work of plagiarism and invention | Public Domain

When recent controversy over Confederate symbols prompted the National Audubon Society to publicly address Audubon’s equally troubling legacy of racism and slavery, there was no mention of the other elephant (bird) in the room. Predictably, the author of a recent biography downplayed the allegations: “Although the veracity of his science has sometimes been called into question, [Audubon’s] major written work, Ornithological Biography, remains a valuable resource and a very good read.” In other words, pay no attention to that man behind the curtain!

For more than a century, invested people have gone to great lengths to protect Audubon’s scientific legacy, by minimizing (or ignoring) the significance of numerous, obvious red flags of fakery and plagiarism. Even the primary record is not trustworthy: Audubon’s granddaughter destroyed his journals after publishing bowdlerized excerpts that showed “what [she believed] he was and not what others thought he was.” She confessed to a biographer: “I burned it myself in 1895 … I had copied from it all I ever meant to give to the public.” When it comes to Audubon, where there is smoke, there is literally fire.

For those who believe, as I do, that we should refrain from judging historical men by modern standards, remember that modern standards of specimen evidence and peer review were already in use at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (ANSP) before Audubon began publishing. In 1824–25, the French ornithologist Charles Lucien Bonaparte, who did not co-sponsor Audubon’s nomination as sometimes claimed, submitted no fewer than 8 manuscripts for peer review at the ANSP, each advancing scientific ornithology according to contemporary (now modern) standards.

In contrast, Audubon was rejected for ANSP membership in 1824, around the same time as multiple, independent allegations of scientific misconduct were levied against him. Some authors have suggested that the scientists in Philadelphia were biased against Audubon for personal reasons, but this betrays a basic misunderstanding (or denial) of the history of American science. Philadelphia was the first city in the United States to adopt the modern standards of specimen evidence and peer review, which later expanded to other cities around the nation. Not only did Audubon fail to meet those known standards; he responded by publishing fraudulent species, with fabricated data, for personal gain.

It is time to come clean about the real myth of Audubon: his scientific integrity. Organizations that use Audubon’s brand, that have contributed to perpetuating his legends, will have to decide whether to symbolically realign themselves with the values of science that are fundamental to their missions. The re-branding of the National Audubon Society would signal a sincere commitment to the science that underlies their important work, to conserve and protect wild bird populations through (fact-based) education and action. Simultaneously, it would demonstrate that a recent public statement supporting the removal of non-physical monuments to white supremacy was more than lip service: “And it’s not just an issue of physical monuments: Many birds are named for human beings (mostly white men), some of whom did terrible things during their lives.” Surely, scientific fraud is included in that list of terrible things.

The conservation movement will not falter if the Audubon monuments are brought down. On the other hand, to leave them standing requires a commitment to miseducation, to keeping the legends of Audubon on life support, despite overwhelming evidence of his sustained, anti-scientific behavior. Behind the veneer, Audubon was a man who consistently and deviously violated the founding principles of scientific ornithology. For that, he does not deserve our veneration.

In summary, Audubon’s scientific legacy is consumed by doubt, and his writings are a quagmire from which few reliable facts can be extracted. To pretend otherwise, at this point, would be disingenuous. But, he was a talented painter!

Reference

Halley, M.R. 2020. Audubon’s Bird of Washington: unravelling the fraud that launched The birds of America. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club 140: 110–141. VIEW

Image credit

Featured image: Portrait of Audubon and The Bird of Washington | Public domain