Where do Slender-billed Curlews breed?

with input from

Alex Bond, Nicola Crockford

RSPB Centre for Conservation Science, U.K.

Geoff Hilton

Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust, U.K.

Johannes Kamp

Biodiversity and Ecosystem Research Group, Institute of Landscape Ecology, Münster University, Germany

James Pearce-Higgins

British Trust for Ornithology, U.K.

LINKED PAPER

The potential breeding range of Slender-billed Curlew Numenius tenuirostris identified from stable-isotope analysis. Buchanan, G.M., Bond, A.L., Crockford, N.J., Kamp, J., Pearce-Higgins, J.W. & Hilton, G. 2017. Bird Conservation International. DOI: 10.1017/S0959270916000551. VIEW

The critically endangered Slender-billed Curlew, Numenius tenuirostris, is perhaps the most enigmatic species of the western Palaearctic region. It was formerly a widespread winter visitor to the Mediterranean basin and other areas of North Africa and the Middle East. The reason for its decline has always been unclear, but it was suggested that the species was becoming less abundant by the early 20th century.

There have been no unequivocal records since 1995, yet every few years there are intriguing reports of possible sightings. Finding any remaining birds is without doubt the greatest priority. Only then can conservation measures be initiated. It is also perhaps the most sought after species for birders in the western Palaearctic. Recently, a huge volunteer effort saw large parts of the species’ historical non-breeding range surveyed (Crockford & Buchanan 2017). Despite counting of over half a million birds at over 680 sites, none of the surveyors saw a slender-billed curlew. However, the non breeding range is vast, and birds might have been overlooked.

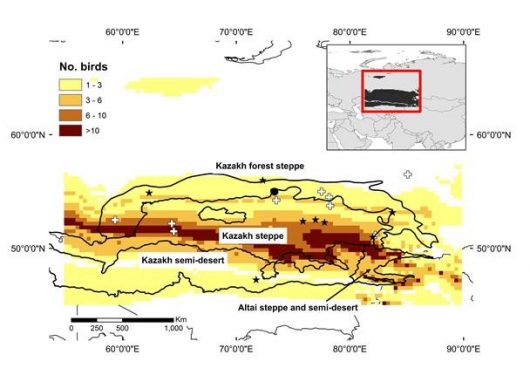

The breeding ecology of the species is practically unknown. Only a handful of nests are known about, and these come from observations by a single observer, V.E. Ushakov. He reported finding nests near the town of Omsk in southern Russia (see map below). Subsequent searches around this area have failed to locate evidence of breeding Slender-billed Curlews. There remained doubt as to whether these were indeed the core breeding areas for the species.

Field searches for the breeding sites of what is clearly now an extremely rare bird, across the vastness of western Siberia, seemed like an expensive and futile exercise. An alternative approach was needed. In 2003, the RSPB, working with colleagues in Russia and Kazakhstan, embarked on a project to identify what might have been the breeding areas of the species, using stable-isotope analysis to identify candidate breeding areas (Buchanan et al). The ratios of naturally occurring stable isotopes in the environment (e.g. 15N vs 14N, 13C vs 12C) vary geographically (and between habitats). On the basis that ‘you are what you eat’, the stable isotope ratios in the tissues of animals reflect those of the environment in which they grew those tissues: they become a chemical signature of the location or habitat which the animal was living in. In the case of continuously regenerating tissues, like blood, liver or muscle, the stable isotope signature is continually ‘updated’ as the tissue is recycled, so they tend to reflect the animal’s recent location. By contrast, bird feathers are inert once grown, and so fix the isotopic signature of the place in which they grew, even if the bird moves elsewhere. In recent years, this phenomenon has been used to identify unknown features of birds’ geographic ranges: if you can catch your bird in winter and test the isotope ratios of one of its summer-grown feathers, you can uncover the breeding grounds.

In the case of Slender-billed Curlew, there are no living birds to catch. But there are over 100 museum skins scattered across Europe, dating from the 19th and early 20th century. We reasoned that the feathers of these birds must retain the isotopic signature of the place they were grown. If that bird was a first winter bird, then by definition its flight feathers must have been grown at the breeding grounds. So museums across Europe were asked to provide samples of primary feathers from Slender-billed Curlews. The idea was to place the isotopic signatures of these feathers onto maps of isotopic gradients in western Siberia (‘isoscapes’). But these maps need calibrating to real world wader feathers from the region, so field teams set off to collect samples of waders in the field in Russia and Kazakhstan. Fieldwork was not without problems, and the help of locals sometimes required.

The teams in Russia and Kazakhstan collected feathers from a wide variety of waders, together with the GPS coordinates of each sample (to calibrate feather values to isoscape values). The samples collected by the field teams and the feather samples supplied by the museums were passed to our colleagues at Iso-Analytical, who undertook the stable isotope analysis. After testing multiple modelling methods to map the potential range, we finally settled on and approach that used only hydrogen isotopes. And then the results surprised us – the area to which most Slender-billed Curlew juveniles were assigned was to the south of the known breeding area. Certainly the area around Omsk was predicted to potentially be the source of some birds, but the main area was further south in the Kazakh steppes. Consequently, we re-ran the analysis just to be sure and the same answer came out again. The area with the largest number of birds assigned to it was in northern Kazakhstan.

The area remains extensive, and more detailed analysis of this area would be needed to identify potentially pristine habitats to which surveys could be targeted, but it certainly shifts the focus of the search. This area has a history of hiding populations of critically endangered birds – intensive field work in this broad area indicated that there are many more Sociable Lapwings, Vanellus gregarius, than previously thought. So there remains hope. And does this get us any closer to the reason for the decline? Since the paper was published in Bird Conservation International, I have found a reference to the 1829 expedition of Alexander von Humboldt to the area. In his notes of the trip he recorded the widespread loss of natural habitat. Could the conversion of its breeding grounds contributed to the decline?

It might not be professional ornithologists who rediscover the species. There are multiple examples of where it has been determined birders who have relocated species that had not been seen for many years. So we encourage all birders visiting or working in this area to keep an eye out for Slender-billed Curlews. Anyone seeing a potential Slender-billed Curlew anywhere should take detailed notes and photographs. These will be essential to assess the veracity of the record. They should contact the Slender-billed Curlew Working Group without delay. Further information on Slender-billed Curlews, including a downloadable identification leaflet can be found at www.slenderbilledcurlew.net.

We are very grateful to all of the individuals who collected field data, and to the museums who generously donated feather samples for analysis. We are also grateful to Iso-Analytical for undertaking the stable isotope analysis.

References

Buchanan, G.M., Bond, A.L., Crockford, N.J., Kamp, J., Pearce-Higgins, J.W. & Hilton, G. 2017. The potential breeding range of Slender-billed Curlew Numenius tenuirostris identified from stable-isotope analysis. Bird Conservation International. DOI:10.1017/S0959270916000551. VIEW

Crockford, N.J. & Buchanan, G.M. 2017. Volunteer survey effort for high-profile species can benefit conservation of non-focal species. Bird Conservation International 27: 237-243. VIEW

Image credit

Featured image: Slender-billed Curlew, Numenius tenuirostris, Merja Zerga, Morocco, 1995 © Chris Gomersall

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.