Does nest monitoring by researchers badger Whinchats?

LINKED PAPER

Nest monitoring does not affect nesting success of Whinchats Saxicola rubetra. Border, J.A., Atkinson, L.R., Henderson, I.G., Hartley, I.R. 2017. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.12574. VIEW

“I have a brilliant idea! We can’t use a live predator to assess Whinchat responses to a predation threat – so how about I dress up as a badger?”

In hindsight, this suggestion may arguably represent the point of my PhD where I started to doubt my sanity a bit. As I sat in front of my supervisor in the pre-fieldwork meeting in 2013, trying to persuade him that this was in fact a reasonable and practical solution to our research problems while he struggled to keep a straight face, it certainly felt like I might be slightly losing it. This feeling only got stronger as the meeting continued; indeed later on, after he calmly pointed out a series of reasons why dressing up as a badger probably wasn’t a viable research technique, all I could think of as a response was to suggest that perhaps instead what we really needed was a remote-controlled car, dressed as a badger.

While to this day I still insist that it was a perfectly sensible research suggestion (which would clearly have worked) by the end of the meeting we’d come up with a perhaps more plausible plan, involving me visiting the nests (in regular clothes) to test the effect of researcher visits instead. This is arguably more important to investigate than the effect of a predator, as we can change our monitoring behaviour to reduce researcher visit effects, but it is much more difficult to do anything about predator disturbance effects.

Nest visits are nearly always required to calculate reliable estimates of breeding success. There is some ambiguity as to whether such visits have a detrimental effect, and findings from other studies are conflicting (Weidinger 2008, Ibanez-Alamo et al. 2012). Some studies even suggest that nest visits may reduce predation risk because human scent trails act as a deterrent to predators. Either way, the breeding success results could be biased. Additionally, visiting nests during the nestling phase may cause a temporary cessation of provisioning by the parents because they interpret human visits as a predation threat, so they switch to defensive and vigilance behaviours (Frid & Dill 2002, Price 2008). This could affect the offspring’s condition and future fitness. Because of this uncertainty it is really important that anyone conducting a prolonged monitoring project assesses whether or not they are affecting the breeding success of their study species.

We measured the impact of our visits to Whinchat nests in two ways. First, during the incubation phase, we visited half the nests every other day and half of the nests were not visited between finding and the estimated hatching date. Instead, we assessed whether these nests were still active from a distance by watching the parents’ behaviour. Second, during the nestling phase, we visited the nest on three consecutive days (when the nestlings were 5,6 and 7 days old), used a video camera to record provisioning rates, and monitored the distances of the parents from the nest over the hour after the visit.

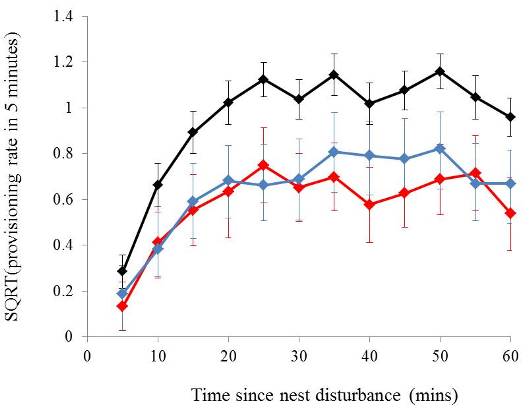

Our results were encouraging. We found no difference in nest success between visit and non-visit nests. Provisioning by parents did decrease temporarily following a nest visit but returned to normal within 20 minutes (Fig. 2) and the adults compensated for the temporary decrease by feeding at a slightly higher rate for a short time afterwards.We calculated that only 0.52% of the nestling period would be affected by the three nest visits we routinely made. We also tested for differences in the response of the parents to nest disturbance depending on their sex or on the condition of the nestlings but did not find any significant effects.

Figure 2 The square-root-transformed mean provisioning rate for all provisioning (black), male provisioning (blue) and female provisioning (red) over all nests in each five-minute period since the nest disturbance event. The bars display the 95% confidence intervals

Figure 2 The square-root-transformed mean provisioning rate for all provisioning (black), male provisioning (blue) and female provisioning (red) over all nests in each five-minute period since the nest disturbance event. The bars display the 95% confidence intervals

In the future, as technology advances, it may be possible to avoid nest visits and get good survival estimates from remote cameras, but until then researchers will need to keep visiting nests to get reliable estimates. In our paper we found that these visits did not affect Whinchat nesting success but, as other studies have suggested, results may differ for other species and other habitats. We would strongly recommend that all researchers undertaking a prolonged monitoring program do a similar experiment to the one outlined here to ensure they are not impacting the breeding success of their study species.

Or, if all else fails, it’s time to get creative. Perhaps the badger suggestion may seem a little unusual – yet, when I was writing up this study and researching papers on the effects of disturbance, I came across an amazing paper by Reimers & Eftestøl (2012), which was awarded an Ig Nobel award in 2014. In this paper, researchers had dressed up as polar bears using rolls of white cloth (Fig. 3) and assessed how this affected the behaviour of Reindeer on Svalbard. This paper is one of the most unusual I have ever read (and certainly the most entertaining) – though I have to admit I’m not confident that the reindeer would actually have mistaken the man in white for a polar bear!

References

Frid, A. & Dill, L. 2002. Human-caused disturbance stimuli as a form of predation risk. Conservation Ecology 6: 11. VIEW

Ibanez-Alamo, J.D., Sanllorente, O. & Soler, M. 2012. The impact of researcher disturbance on nest predation rates: a meta-analysis. IBIS 154: 5-14. VIEW

Price, M. 2008. The impact of human disturbance on birds: a selective review. In Lunney, D., Munn, A., Meikle, W. eds. Too Close for Comfort : Contentious Issues in Human-Wildlife Encounters. Royal Zoological Society of New south Wales, Mosman, pp 163-196.

Reimers, E. & Eftestøl, S. 2012. Response behaviors of Svalbard Reindeer towards humans and humans disguised as Polar Bears on Edgeoya. Arctic Antarctic and Alpine Research 44: 483-489. VIEW

Weidinger, K. 2008. Nest monitoring does not increase nest predation in open-nesting songbirds: inference from continuous nest-survival data. Auk 125: 859-868. VIEW

Image credit

Featured image: Whinchat, Saxicola rubetra, feeding nestling © Jennifer Border

Blog posts express the views of the individual author(s) and not those of the BOU.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.