GPS-tracking reveals non-breeding locations and apparent molt-migration

LINKED PAPER

GPS-tracking reveals non-breeding locations and apparent molt migration of a Black-headed Grosbeak. Siegel, R.B, Taylor, R., Saracco, .F., Helton, L. & Stock, S. 2016. Journal of Field Ornithology. DOI: 10.1111/jofo.12149 VIEW

Identifying the breeding areas, migration routes, and wintering grounds of particular bird populations has become a major frontier in ornithology. Recent progress in miniaturizing archival global positioning system (GPS) units provides the opportunity to track individual birds across their annual cycle with unprecedented precision. Such precise tracking can yield a more nuanced understanding of the annual migratory cycle of birds, which may involve migration strategies that are more complex than simply migrating between a breeding location and a wintering location.

One such migration strategy is molt-migration, in which birds pause to complete their prebasic molt at a location between their breeding and wintering grounds. In a recently published study, scientists at The Institute for Bird Populations and Yosemite National Park describe the year-round movements of a Black-headed Grosbeak captured and GPS-tagged (with a miniature tag produced by Lotex Wireless Inc.) in the park during the 2015 breeding season and then recaptured one year later.

© Chris Hubach.

Data from the recovered tag showed that the bird spent at least two months in Sonora, Mexico during the ‘North American Monsoon’ season in the late summer and fall, flew another 1,300 km south in the late fall/early winter to spend the winter in the Michoacan-Jalisco border region, and then returned to Yosemite the following spring.

Figure 2 Recorded locations throughout the annual cycle of a Black-headed Grosbeak GPS-tagged and recaptured a year later at Hodgdon Meadow, Yosemite National Park, (inset)

These data are consistent with the expected seasonal timing and duration of movements of a molt-migrating bird, and represent the first time breeding, molting, and wintering sites have been identified to pinpoint accuracy for a western Neotropical migrant bird across the annual cycle.

Figure 3 Aerial imagery of landscapes around Black-headed Grosbeak tracking locations in Yosemite National Park (A), Sonora, Mexico (B and C), Michoacán, Mexico (D), and Jalisco, Mexico (E and F). Panel F provides a close-up view of the same locations as Panel E

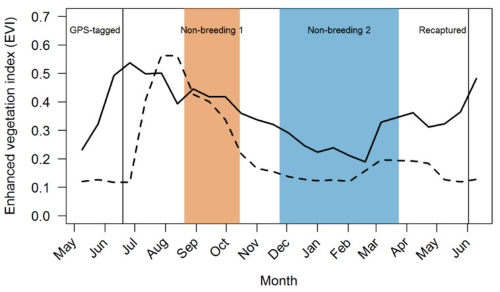

We assessed seasonal patterns of vegetation greening at the recorded grosbeak locations during the non-breeding season using 16-day 0.25-km resolution Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) data derived from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instrument of NASA’s Terra satellite (MODIS product MOD13Q1). EVI, a composite metric of vegetation greenness, incorporates structural and seasonal components of habitat quality, including primary productivity (leaf chlorophyll content), leaf area, canopy cover, and vegetation complex. EVI values varied greatly throughout the year in both the presumed molting grounds in Sonora and wintering areas in Michoacán and Jalisco, but the variation was more pronounced in Sonora.

Figure 4 Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) data obtained from May 2014 to June 2015 at locations in Mexico where a male Black-headed Grosbeak captured and GPS-tagged in Yosemite National Park spent the presumed molting period (dashed line) and the remainder of the winter (solid line). Orange and blue shaded areas, respectively, represent the minimum period of time the bird spent in Sonora (Non-breeding 1), and then near the border between Michoacán and Jalisco (Non-breeding 2)

Both sites exhibited peak EVI values in the summer, with the peak occurring about 1.5 months later in Sonora. Both sites, but especially Sonora, had much lower values in the winter. The grosbeak was first recorded in Sonora just after the local EVI value peaked and began to decline, although it could have arrived there sometime during the previous weeks when the index was at or approaching its peak. The bird remained in Sonora throughout most of the subsequent decline in the index, and then departed sometime between October 16 and November 24, shortly before the lowest values of the year were obtained. EVI values at the bird’s wintering area in Michoacán and Jalisco were also at their lowest annual levels while the bird remained there throughout the late winter and early spring, but values were nevertheless substantially higher than at the Sonora location during the same period. The greening of the monsoon region likely provides an intense, but ephemeral pulse of food and cover that molt migrants need during this vulnerable life-history stage. The grosbeak we tracked arrived in the region around the time when the EVI reached its peak, and then departed shortly before the index exhibited its lowest values, suggesting a possibly important match between migration timing and monsoon-driven phenology.

During the coming decades, anthropogenic climate change is projected to have little effect on overall precipitation associated with the North American Monsoon, but to substantially change its seasonal timing. Models project significant declines in early monsoon (June-July) precipitation and concomitant increases in late monsoon (September-October) precipitation, yielding an overall delayed onset and end of the monsoon. This shift in timing could cause difficulties for Black-headed Grosbeaks and other molt-migrants, especially because spring-like conditions across breeding ranges in much of western North America are beginning and ending increasingly earlier due to climate change, with hot, dry summer conditions starting earlier and lasting longer. Many western North American molt-migrant species may thus be facing pressures to breed earlier and then depart earlier from breeding areas as moisture and food decrease, even while moisture availability and greening in their molting areas is occurring increasingly later. It is unclear how or whether molt-migrant species will be able to adapt to the temporal disjunction between the need to migrate and the availability of plentiful food and cover in the molting areas that is likely to result.

Reference

Siegel, R.B, Taylor, R., Saracco, .F., Helton, L. & Stock, S. 2016. GPS-tracking reveals non-breeding locations and apparent molt migration of a Black-headed Grosbeak. Journal of Field Ornithology. DOI: 10.1111/jofo.12149 View

Image credit

Top image: Black-headed Grosbeak, Pheucticus melanocephalus © Alan Harper.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.